Early reexamination study:

1. Do the 22 measures on the 5Essentials Survey remain predictive of school improvement and student outcomes?

Extended reexamination study:

1. Do the 5Essentials predict school improvement in high- and low-poverty schools?

2. Regardless of poverty level, does every school have a similar likelihood to develop or maintain strong 5Essentials?

Qualitative study on survey practices in schools:

1. How do schools understand and utilize data from the 5Essentials Survey in the context of improvement efforts?

2. What factors facilitate or impede schools’ engagement with their 5Essentials results?

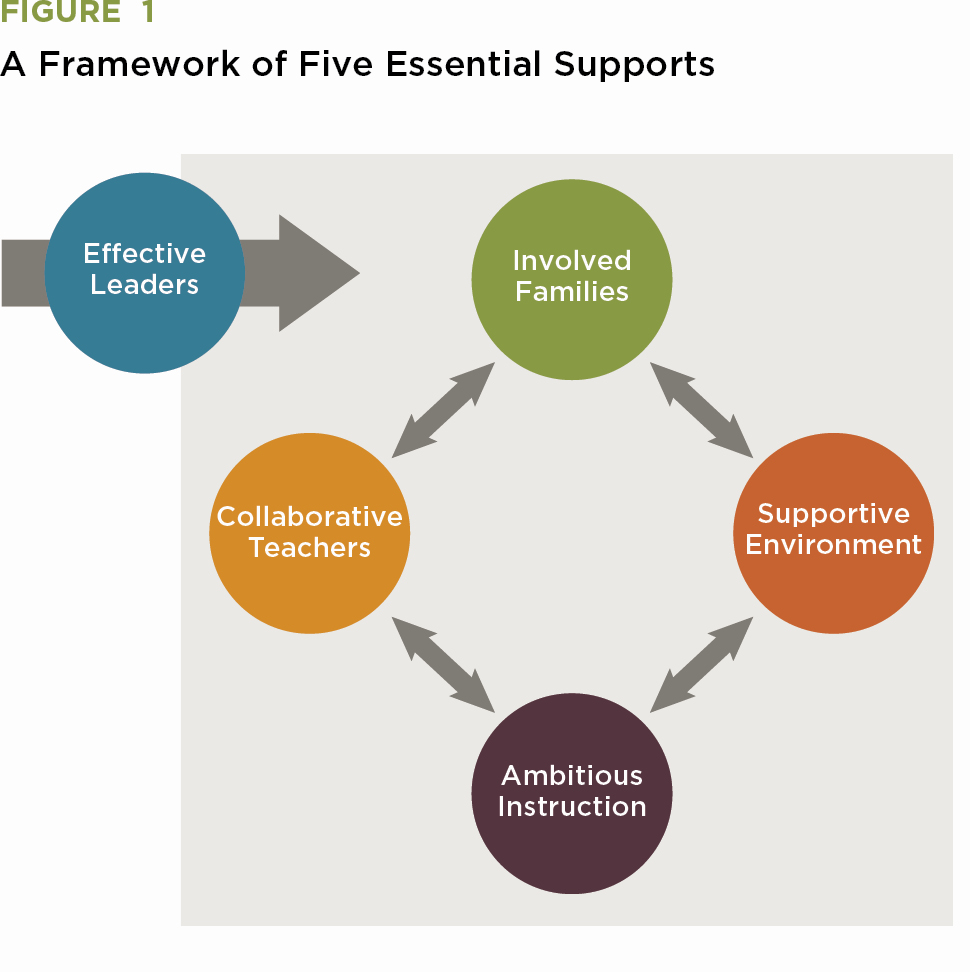

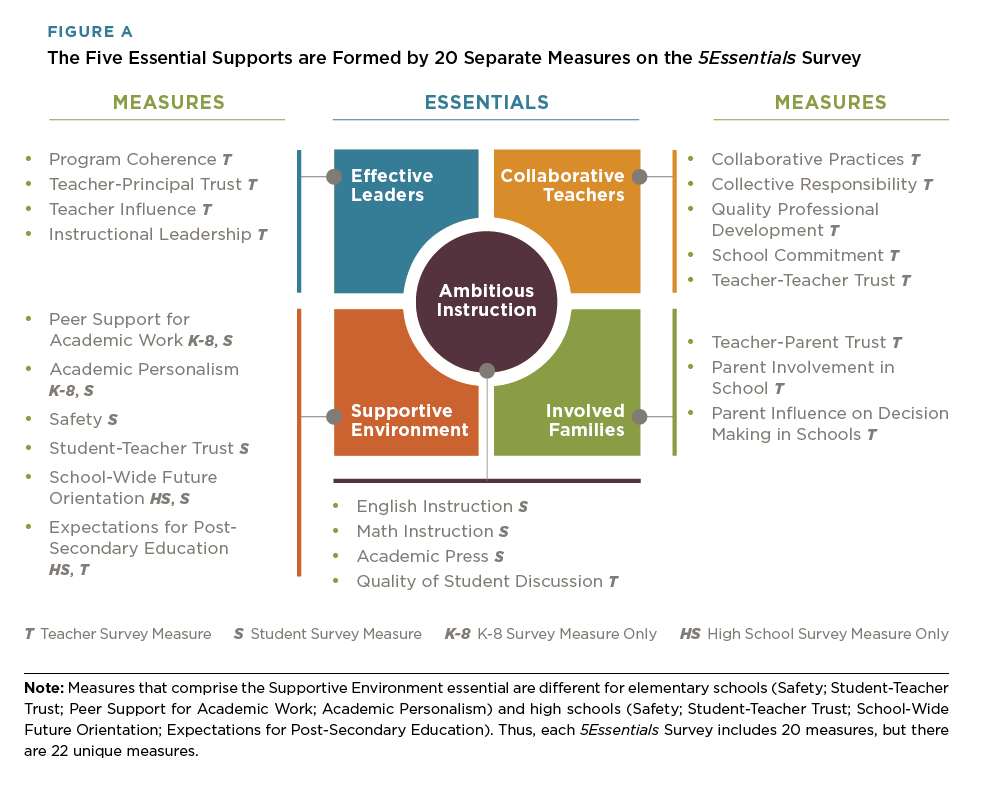

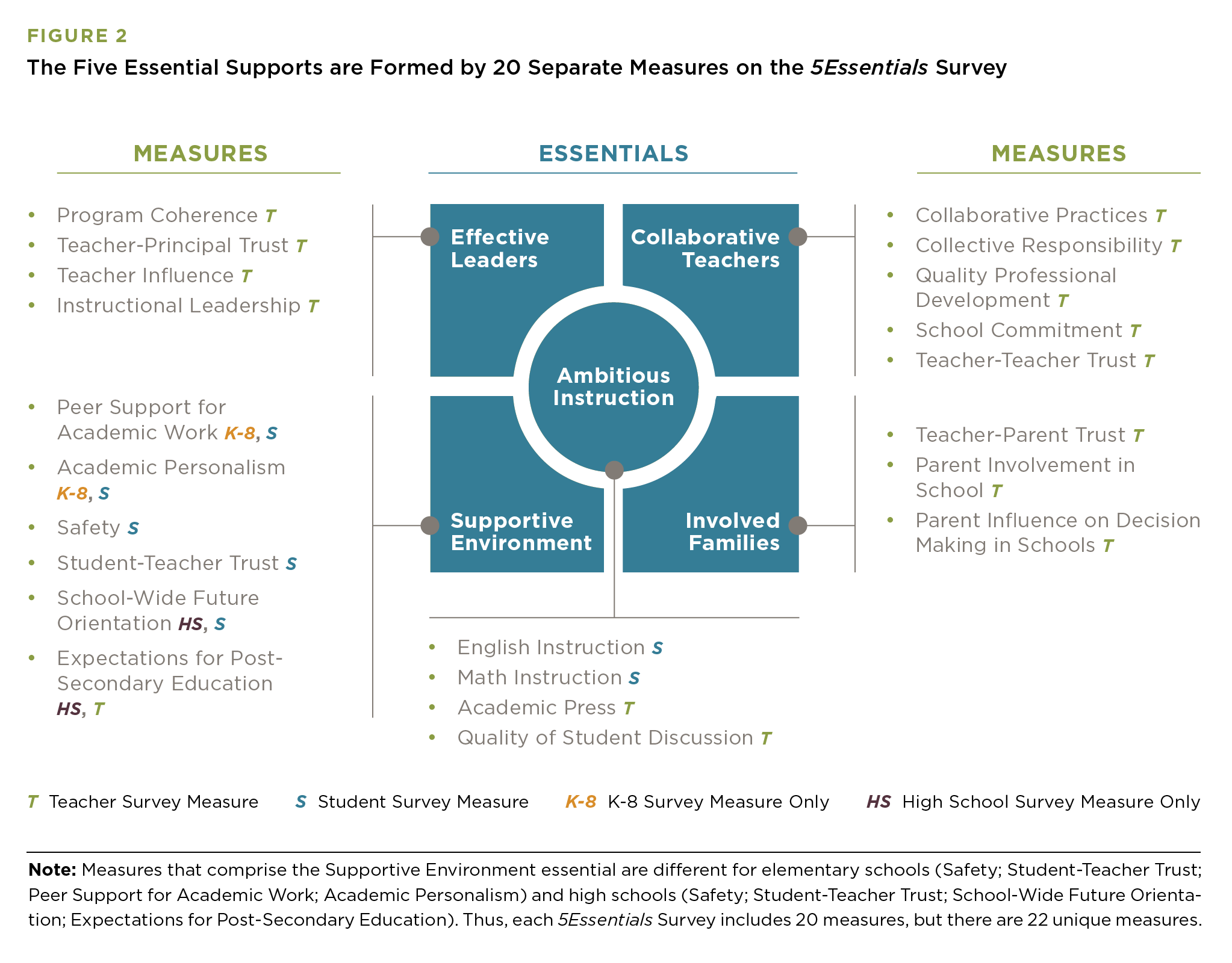

The 5Essentials Survey has been administered in CPS since the 1990s and measures a school’s strength in five essential organizational conditions that influence student learning: Effective Leaders, Collaborative Teachers, Involved Families, Supportive Environment, and Ambitious Instruction.

This study uses both quantitative and qualitative methods to address questions about the survey’s predictiveness and how schools utilize the data generated by the survey.

- The early reexamination study uses data from 2014–19 seeks to understand the validity of the 5Essentials Survey at the present stage of educational practice in both elementary and high schools, and under present conditions in CPS.

- By revalidating the 5Essentials Survey, and expanding the validation to more grade levels and student outcomes (test scores, attendance, GPAs, Freshman OnTrack rates, and college enrollment), this study seeks to provide school leaders, teachers, researchers, and other education practitioners the needed data to guide their work building schools in which adults and children can learn and thrive.

- The extended reexamination study used pre-pandemic data from 2011-12 through 2018-19 to examine whether the 5Essentials predict school improvement in high- and low-poverty schools, and whether every school has a similar likelihood to develop or maintain strong 5Essentials, regardless of poverty level.

- Using interviews conducted throughout 2019, the qualitative study examines how schools understand and utilize data from the 5Essentials Survey in the context of improvement efforts, and what factors facilitate or impede schools’ engagement with their 5Essentials results.

Read our Chicago Sun-Times op-ed, Let’s pay attention when students, teachers tell us what they think about their school, to hear from our Lewis-Sebring Director, Elaine Allensworth, on the importance of these findings.

Key Findings

Reexamination report:

- 5Essentials Survey measures continue to be predictive of school improvement in elementary schools, and are also predictive in high schools.

- Of the 22 survey measures, all were in some way positively and significantly associated with schools’ improvement. At the same time, all measures were not associated with all outcomes.

- Both 1) starting out the year with strength in 5Essentials Survey measures and 2) improving on measures during the course of the year predicted improved student outcomes in schools.

- The 5Essentials Survey measures were positively and significantly related to growth in elementary test scores and attendance.

- Elementary GPA also improved more in schools with strong 5Essentials Survey measures.

- High school outcomes—attendance, test scores, GPA, Freshman OnTrack, and college enrollment—were positively and significantly related to 5Essentials Survey measures.

- 5Essentials Survey measures predicted improvement for schools that were strong compared to other schools, but also for schools compared to themselves in stronger vs. weaker years.

Quantitative study, 5Essentials Survey in CPS: School Improvement and School Climate in High Poverty Schools:

- The 5Essentials Survey remains strongly predictive, despite concerns about its inclusion in CPS accountability.

- 5Essentials measures predicted school improvement on an array of outcomes—including GPA, attendance, and test scores—in both high- and low-poverty schools at both the elementary and high school level.

- In most 5Essentials Survey measures, chances of being strong on the 5Essentials were found to be similar for schools at all poverty levels.

- At the same time, there were some measures that were more likely to be strong in schools with students from neighborhoods with lower poverty levels.

- Five of these measures were less prevalent in both high-poverty elementary and high schools.

- These included one student measure—Safety—and four teacher measures—Parent Involvement, Teacher-Parent Trust, School Commitment, and Student Discussion.

- Among elementary schools with strong 5Essentials, high-poverty schools improved more than low-poverty schools on more than one-half of measures.

- This means that improvements in school climate and organizational features in high-poverty schools had a greater benefit for student learning than in low-poverty schools.

Qualitative, 5Essentials Survey in CPS: Using School Climate Survey Results to Guide Practice:

- CPS granted schools considerable autonomy in how they used their survey data. However, principals acknowledged that the lack of district-wide guidance on how to interpret and act on the results hampered use of the data for improvement.

- Practitioners reported that the data sometimes seemed opaque and difficult to use. They also noted that its focus on school principals made it difficult for school leaders and their teams to engage impartially with the data.

- Principals credited partnerships with leadership coaches from external organizations as valuable in helping them interpret and act on their survey data. Similarly, systematic collaboration by instructional leadership teams increased schools’ capacity to use the data.

- Some principals depicted their priorities for school improvement as heavily influenced by SQRP and accountability, and some teachers expressed concern that accountability affected how teachers responded to the survey.